Abby Kalscheur (’11 BS ALS) may never forget following the spry Guatemalan farmer up the side of a volcano to his milpa, a small subsistence farm. Twenty students and three faculty members struggled to keep up with the father of 10, who on many days will make nine or 10 trips to carry fertilizer up the two-mile trail, then make as many trips carrying his produce back down.

”Smell it, it’s good,” the farmer urged Professor Caitilyn Allen as he proudly held a handful of the rich, volcanic soil that allows him to feed his family and have produce to sell. Watching the farmer, Kalscheur, who double majored in plant pathology and agricultural economics, understood that her research to improve farming technology could help subsistence farmers like the ones she met. “I have training to make a difference,” she said.

Professor emeritus Douglas Maxwell wants to ensure students like Kalscheur have the benefit of studying abroad. He and his wife, Martha, established the Douglas and Martha Maxwell Educational Opportunity Award to support scholarships in the Department of Plant Pathology, with preference given to research or international education experiences.

“Without encouragement from my own undergraduate professor, I’d never be sitting here,” Maxwell said. “A research project or an international experience can change the lives of young people. It can give them direction and purpose in their future education.”

Maxwell, who co-led the Guatemala trip, has been involved in international agriculture since 1984 and began a project in Guatemala in 1998 to breed tomatoes resistant to tropical diseases. The tomatoes are doing well. Maxwell’s gift is among several private funds that reduce the cost of the international trips for the participating students.

“I don’t think I would’ve been able to take the class without (financial help),” Kalscheur said.

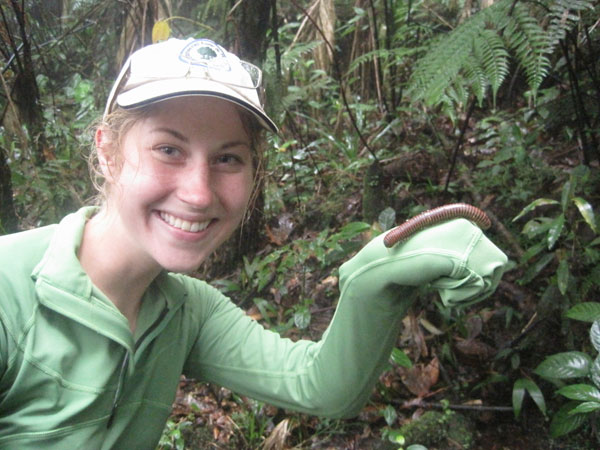

The 20 University of Wisconsin-Madison tropical plant pathology students studied Guatemalan agriculture, history and plant diseases during the fall semester, then spent 15 days in the Central American country this spring, visiting a variety of food production facilities, from traditional farms to industrial operations. “I learned more in 14 days than in the entire semester,” said Kalscheur, one of two undergraduates on the trip who also benefitted from the older students’ research experience. “It was a crash course in plant pathology applied in the field.”

On the volcanic hillside, the farmer grew corn, black beans, squash and nispero, a fruit tree, in what Allen called a “pretty sophisticated cropping system.” The corn needs nitrogen from the beans; the beans climb up the 8-foot corn stalks, and the large leaves of squash reduce weeds and water loss. Corn stalks also are used for roofing and fencing.

Students also visited large-scale sugar cane, banana and coffee plantations, a cooperative of Mayan villages that grows and exports snap peas, green beans, mini squashes and tiny carrots, and massive greenhouses for growing poinsettias and other ornamentals.

Students encountered a lot of biology and diseases, learned disease management and saw the social and economic systems that support agriculture, Allen said. The trip showed students that their work is about more than coaxing another couple pounds of produce from an acre of ground, she added.

Students encountered a lot of biology and diseases, learned disease management and saw the social and economic systems that support agriculture, Allen said. The trip showed students that their work is about more than coaxing another couple pounds of produce from an acre of ground, she added.

In Guatemala, more than half the population lives on less than $2 a day and half of children 5 and younger are malnourished, Allen and Maxwell said. Food and well-being are tightly tied together, and subsistence farms like the ones the students visited provide 62 percent of the nation’s food.

To go into an area where agriculture is tied to daily lives shows students that their work also has an enormous social impact, Allen said. “They get passionate in the course of this trip,” she said. “I hope that they recognize they can do something with agriculture research and outreach that has a human impact.”

The Guatemala field courses are planned in conjunction with San Carlos University in Guatemala City, and San Carlos students also visit the UW-Madison. “The trips have convinced students to devote their careers to international agriculture,” Maxwell said. “Whatever they do, it’s pretty hard to be successful in our world without an appreciation of other countries. This starts them on that path.”

The trip changed Kalscheur’s career plans. “There’s a distinct need for tropical plant pathologists,” she said, adding that the warmer climates are prone to higher disease and pest populations. “That class opened up my eyes in ways I still don’t finally understand.”