An experimental device stimulates nerves in the tongue, allowing Ron Husmann, who lost his voice to multiple sclerosis, to sing again after 27 years of whispers and silence.

First, there was the voice, a full, rich bass, the kind of voice that makes audiences swoon within a few measures and can fill a 3,000-seat theater with no microphone. Robert Goulet grew famous with that kind of voice, but Goulet never lost his magnificent sound.

Broadway singer Ron Husmann – his star traveling with Hal Prince, Ethel Merman, Bernadette Peters, Juliette Prowse, Debbie Reynolds – wasn’t so lucky.

In 1981, two decades after Prince discovered him, Husmann’s voice cracked. He lost his middle range that year; even a microphone couldn’t help in 1982. Whispers and silence followed.

Fast forward to April 2009. When Husmann arrived at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Tactile Communication and Neurorehabilitation Laboratory (TCNL), multiple sclerosis had left him unable to walk a straight line or turn easily, even with a cane, and speech was limited to five minutes and, then, only softly.

An experimental treatment coupled physical therapy with stimulating the nerves in Husmann’s tongue. By the fourth session, he was in tears.

“I could sing. It wasn’t great, but I could at least make notes connect. I had a complete breakdown. They stood there and stared at me, while I just sobbed.”

Ron Husmann

“I could sing,” he said. “It wasn’t great, but I could at least make notes connect. I had a complete breakdown. They stood there and stared at me, while I just sobbed.”

This is where the amazing plastic brain comes into play, said Mitch Tyler, a TCNL scientist. “The brain is a very adaptive, very malleable structure. When there’s a trauma, it’s like the neurons and their support cells go offline. We’re getting the brain and body to talk to each other again.”

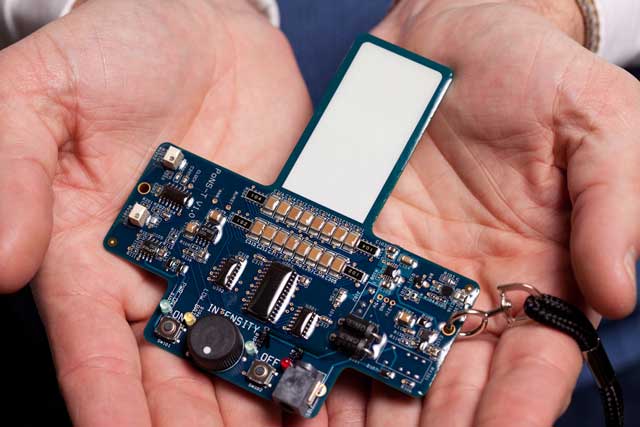

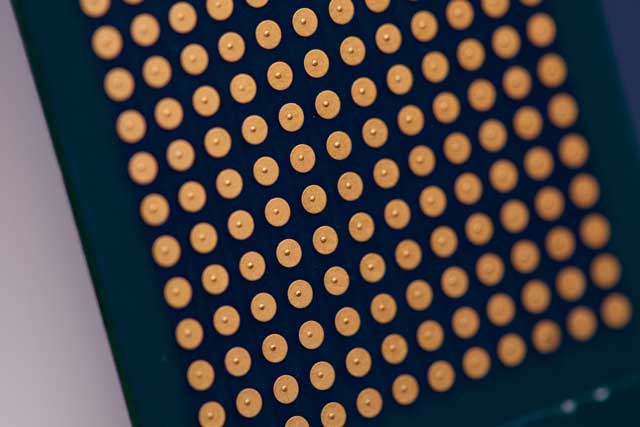

And it’s all happening by combining movement therapy with a device that stimulates the tongue, where a plethora of nerve endings connect directly to the brain stem.

At TCNL, scientists led by the late Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita first created a device to stimulate the tongue, allowing the blind to “see” without their eyes. Next, people with balance problems used a related device to re-learn balance and how to walk confidently. Today, those with neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis are regaining useful movement, beginning with learning to be aware of their bodies.

Instead of favoring a strong leg, for example, the therapy teaches patients’ brains to rediscover signals from both legs to return to normal walking. Restoring Husmann’s voice included re-teaching the brain how to properly control the breath.

“I feel free. I can walk the dog. I don’t have to worry about falling over, and I always felt like I was going to tip over sideways. The biggest part is I can talk.”

Ron Husmann

“Without a doubt, the results of TCNL’s work are interesting so far,” said Dr. Chris Luzzio, an assistant professor of neurology in the School of Medicine and Public Health. He was interested in TCNL’s work because many effects of MS are linked to the brain stem. Several of his patients participated in TCNL’s initial MS study, and Luzzio was surprised when all of them reported improved walking, balance and quality of life.

“I’d support and encourage further work,” said Luzzio, who is helping to design further, blind clinical trials to eliminate the possibility of a placebo effect.

The therapy TCNL is testing encourages neurons to come back online and return the brain to a normal operating state, Tyler said. He and his TCNL colleagues, Dr. Yuri Danilov and Kurt Kaczmarek, hypothesize that the stimulation unmasks new neural pathways, alerts the brain to existing but weak signals from the body or strengthens existing pathways. In addition to changing how one neuron talks to another, the support structure of the brain also may change to become more efficient, Tyler said.

In addition to testing MS patients, TCNL also has finished preliminary work with those who have had brain trauma or suffered from a stroke. Patients who learned to move better also, surprisingly, reported improved attention, memory, sleep and mood, and a decrease in visual sensitivity to motion, Tyler said.

Yuri Danilov, of the TCNL lab, readies research participant Stuart Brandes for a training session using Cranial-Nerve Non-Invasive NeuroModulation (CN-NINM). Click to view more photos.

For Husmann, the tongue stimulation plus movement training have given him the ability to participate in everyday life again, beginning with putting down his cane.

“I feel free,” he said. “I can walk the dog. I don’t have to worry about falling over, and I always felt like I was going to tip over sideways. The biggest part is I can talk.”

And he can sing, though he said his voice isn’t pretty anymore.

For more information

TCNL scientists talk about the trials and triumphs of bringing a new technology and new company to life as well as exciting possibilities for the future. What our brains currently do for us is amazing. Can we dare to imagine what they are capable of doing if we give them the tools?